Pakistan’s Monsoon Emergency: A New Chapter in a Worsening Climate Crisis

Pakistan is once again grappling with one of the most intense monsoon seasons in its history, reigniting fears of deadly floods in low-lying regions across the country. According to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), 221 people have lost their lives and 594 have been injured due to heavy monsoon rains since June 26, 2025. The province of Punjab has suffered the highest number of casualties, with most fatalities resulting from the collapse of dilapidated homes and structures.

Data from the Punjab Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) reveals that from June 25 to mid-July, 135 people died and 478 were injured in the province alone. The causes of death include 99 from structural collapse, 19 from drowning, 12 from electrocution, and 5 from lightning strikes. Of the injured, 465 were harmed due to building collapses. PDMA officials have stated that, on the Chief Minister’s directives, high-quality medical care is being provided to the injured, and financial compensation between Rs. 1 million and Rs. 5 million is being given to the families of the deceased.

Amid on-going devastation, NDMA has issued a flood alert across various regions, warning that the fourth spell of monsoon rains may continue until at least July 26. Moisture-laden winds from the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, combined with a low-pressure system, are expected to trigger moderate to heavy rainfall across much of the country. Areas at risk include river belts such as Swat and Bannu, with potential flash floods and landslides forecast in hilly regions like Malakand, Swat, and Dir. Major cities including Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, Lahore, and Sialkot are also expected to experience heavy downpours.

These developments are disturbingly reminiscent of the catastrophic floods of 2022, a disaster that submerged one-third of the country, claimed 1,486 lives, and caused economic losses exceeding 30 billion USD. However, the 2022 floods were not simply the result of extreme weather, they were the outcome of a dangerous fusion of climate change, poor urban planning, and unchecked human encroachment on natural floodplains.

A ground breaking study titled “Anthropogenic and Climatic Drivers of the 2022 Mega-Flood in Pakistan” offers critical insights into the science behind that tragedy. According to the study, the 2022 pre-monsoon rains were 111% above the long-term average, saturating the soil before the actual monsoon brought a deluge—547% wetter than average in some southern areas. This intense rainfall coincided with record snowmelt in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan region, where rising temperatures triggered rapid glacier melting and “rain-on-snow” events. The resulting surge pushed major rivers like the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum beyond their capacity. Stream flows at the Sukkur Barrage reached 170% of historical norms, surpassing even the 2010 and 2015 floods.

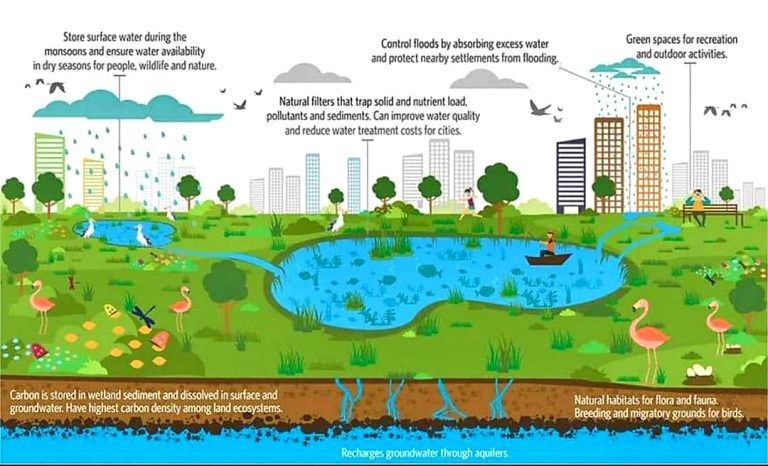

The study’s use of satellite data, rain gauges, and hydrological modelling confirms that this was no isolated incident it was a direct consequence of a warming planet. But climate was only part of the equation. Over the past two decades, riverbank agricultural expansion and unregulated urbanization have narrowed natural flood channels and weakened the land’s ability to absorb excess water. In cities like Larkana, wetlands have been replaced by concrete, and development in floodplains has increased the risk of flash floods and hampered recovery efforts.

Looking ahead, the situation may grow worse. According to CMIP6 climate projections, Pakistan’s five-day rainfall maxima could rise by 58% by the end of the century under a high-emission scenario. One-day rainfall extremes may increase by 44%. Temperature in the Indus Basin could climb as much as 7°C by 2099, accelerating glacier melt and dramatically altering the country’s hydrology.

The consequences are already visible in urban areas. Cities such as Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad and Islamabad suffered from flash floods in 2022 due to clogged drains, informal settlements, and underdeveloped storm water systems. These vulnerabilities are the result of years of underinvestment in climate-resilient infrastructure, particularly in low-income urban neighbourhoods.

The socioeconomic fallout of the 2022 disaster remains deep. Small farmers, daily wage earners, and residents of informal settlements were disproportionately affected. In August 2022 alone, vegetation cover dropped by 40%, damaging food security in key agricultural zones. Economic activity worth over 10 billion USD roughly 2.8% of Pakistan’s GDP was wiped out in a matter of weeks.

This year’s monsoon devastation serves as a stark reminder that climate change is no longer a distant concern but a present and escalating crisis. To prevent future disasters, Pakistan must take urgent and comprehensive action. This includes investing in advanced early warning systems, enforcing zoning laws to restrict construction in flood-prone areas, restoring natural flood defences like wetlands and forests, upgrading urban drainage infrastructure, closely monitoring glacial melt, and actively seeking international climate finance to support both mitigation and long-term resilience efforts.

The 2022 flood was a harbinger of Pakistan’s climate future, a future in which disasters become more frequent, more deadly, and more expensive. As extreme weather events grow in both scale and frequency, Pakistan must treat every crisis as a call to action. Without urgent policy reform, strategic investments, and long-term climate resilience planning, the country risks repeating the same mistakes only at greater costs.