How Carbon Credits Are Driving Landfill Restoration and Sustainability

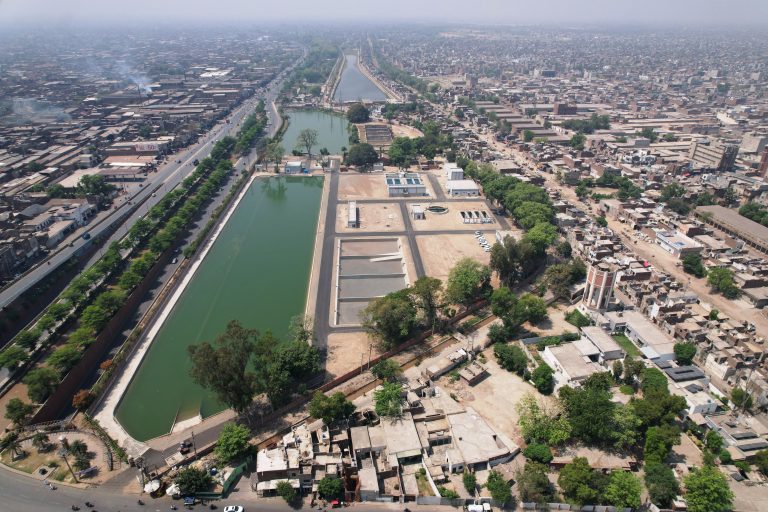

For years, travellers on Lahore’s Ring Road were met with an overpowering stench upon reaching the Mahmood Booti area. This odour emanated from a massive landfill where decades of waste had accumulated into an 80-foot-high mountain, covering 41 acres and holding nearly 14 million tons of garbage.

Beyond the foul smell and unsightly landscape, the landfill posed a greater danger—methane emissions. Unlike carbon dioxide, methane is an invisible yet highly potent greenhouse gas. Over a 20-year period, it traps 80 times more heat than carbon dioxide, making it a significant contributor to global warming.

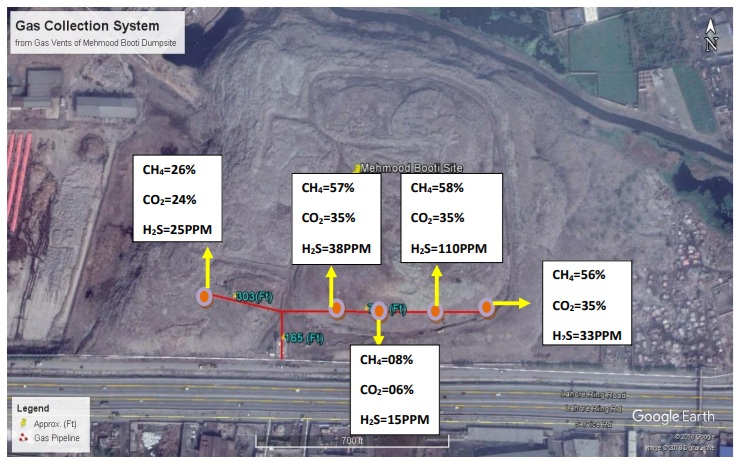

In 2021, satellite data detected alarming methane clouds over Lahore, particularly over Mahmood Booti and the nearby Lakhodair dumpsite. Bloomberg reported a methane bubble measuring 126 metric tons per hour above the landfill, highlighting the environmental risk. That same year, the International Energy Agency ranked Pakistan as the seventh-largest methane emitter globally.

Beyond air pollution, Mahmood Booti also posed a severe threat to groundwater. Rainwater seeping through the waste created leachate, a toxic liquid that contaminated underground water, making it unsafe for consumption.

Today, the towering landfill has disappeared. The once-massive waste site has been covered with soil, eliminating the stench and reducing environmental hazards. While this transformation marks progress, it raises a crucial question: Is this a long-term solution or just a temporary fix?

The Restoration Plan and Renewable Energy Initiatives

Mahmood Booti, Lahore’s oldest landfill, was established in 1998 and officially closed in 2016. However, the massive waste buildup remained a challenge for environmental authorities, contributing to severe air pollution and methane emissions.

Methane released from the landfill not only worsened global warming but also impacted local weather patterns, intensifying smog, especially along the Ring Road. Given Pakistan’s commitment at COP26 to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030, addressing this issue became crucial.

Efforts to curb emissions faced financial challenges, but a breakthrough came when the Lahore Waste Management Company (LWMC), in collaboration with the Ravi Urban Development Authority, launched a restoration project. As part of this initiative, 14 million tons of waste have been buried under soil.

Private companies are executing the project, which is expected to be completed by August at an estimated cost of 1,400 million rupees. The plan includes extracting landfill gas for sale to nearby industries, developing an 11-acre solar park generating five megawatts of electricity, and establishing an urban forest over 30 acres.

Significant progress has already been made, including land levelling, leachate extraction, and the installation of gas vents. Instead of forming large methane clouds, the gas is now being gradually released. Surveys are underway to determine the volume of gas available. If feasible, it will be supplied to industries; otherwise, it will be flared to prevent environmental harm. This initiative marks a shift towards sustainable waste management, reducing pollution while generating renewable energy and green spaces for Lahore.

The Role of Carbon Credits in Financing the Project

According to LWMC CEO Babar Sahib Din, the government is not spending a single penny on the project. Instead, private companies are covering the costs, with compensation coming through carbon credits.

Carbon credits represent verified reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. When a company, individual, or institution undertakes a project that lowers emissions, it generates carbon credits. Each metric ton of reduced emissions equals one credit, which can then be sold on the carbon market. Companies unable to cut their emissions purchase these credits, effectively funding projects that offset their own carbon footprint.

There are two types of carbon markets: regulated markets controlled by governments and voluntary markets. The value of carbon credits depends on project quality and market conditions. Greenhouse gas reduction projects can range from waste management and waste-to-energy initiatives to renewable energy adoption and emission-reducing technologies.

Third-party organizations rigorously verify these projects to ensure they genuinely reduce greenhouse gases. Their impact and effectiveness determine the credits’ market value. Babar Sahib Din stated that carbon credits typically sell for $5 to $50 each, depending on project quality.

Since this is a waste management project, he expects to sell credits for $18 to $20 each. A feasibility study, set for completion in three months, will provide precise estimates. However, initial projections suggest the project could generate between $500,000 and $1 million annually through carbon credits.

Expanding the Model: Lakhodair Landfill and Beyond

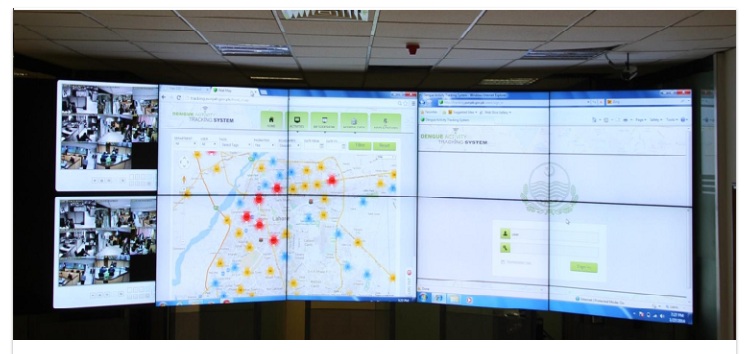

With Mahmood Booti’s transformation underway, another challenge looms. Since its closure, most of Lahore’s waste has been dumped at the Lakhodair landfill, which receives around 5,000 tons of garbage daily. Over the years, millions of tons have accumulated, making it another significant source of methane emissions. Similar unmanaged landfills exist across Punjab’s cities.

LWMC has now set its sights on restoring Lakhodair using the same approach. The German government has funded its feasibility study, and work is already underway. Extracted gas will be supplied to industries, and an urban forest and solar park will be developed in the future. Previously, eliminating such landfills was costly, but with the introduction of carbon credits, similar projects could become financially viable in other locations. Lahore’s success with Mahmood Booti and Lakhodair could serve as a model for sustainable waste management, transforming toxic landfills into sources of renewable energy and green spaces for future generations.