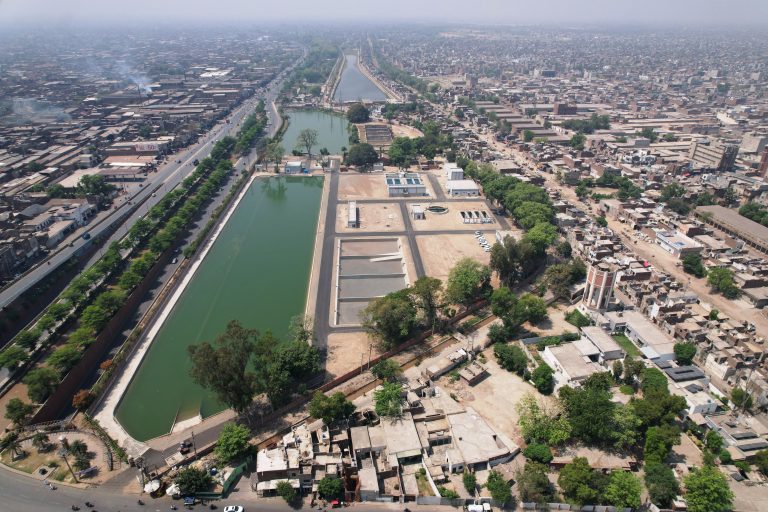

Groundwater Reserves and Pakistan’s Agricultural Economy

In the aftermath of the recent floods, a recurring argument has gained traction on social media, YouTube channels, and even some television debates: Pakistan does not need new dams, because an estimated 500 million acre-feet (MAF) of water is already available beneath our riverbeds, which can be extracted and used.

At first glance, this claim sounds appealing. However, the scientific and hydrological reality is far more complex. The so-called 500 MAF of water is not an annually rechargeable reserve. Rather, it is an accumulated stock formed over centuries through slow river seepage and rainfall infiltration.

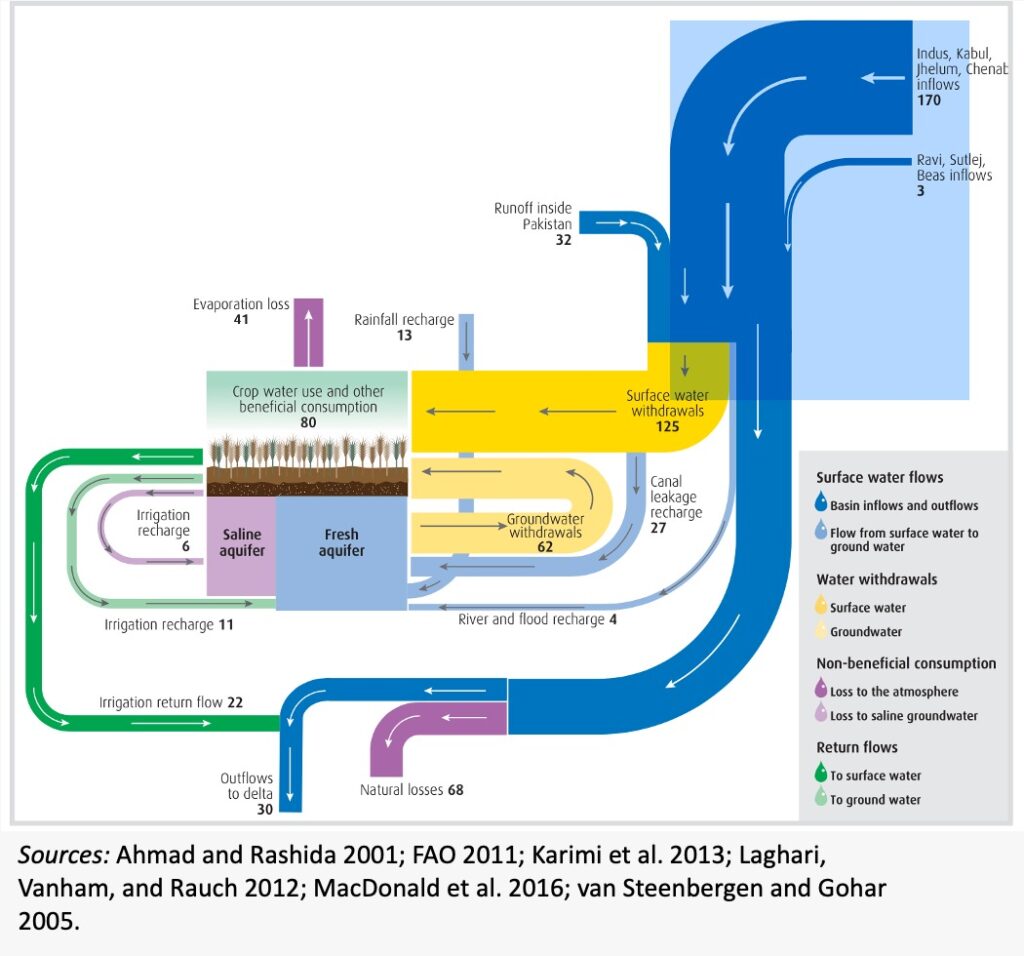

If we break down Pakistan’s groundwater budget, the picture becomes clearer: around 21% is recharged by rainfall, 6% by rivers and floodwater, 47% by the canal irrigation system, and 27% through irrigation return flows. This shows that annual recharge from rivers and floods remains quite limited.

On the other hand, Pakistan’s agricultural economy consumes nearly 64 MAF (80 billion cubic meters) of water annually. Against this, the annual recharge from rainfall and flood seepage amounts to just 13 MAF. In other words, relying solely on groundwater would leave us with an annual shortfall of over 50 MAF. If we were to start pumping out the 500 MAF “reserve” beneath the riverbeds, it would last barely 9–10 years before being exhausted.

Thus, the notion that Pakistan can abandon dams, barrages, and canal systems in favor of underground reserves is a dangerous misconception. Anyone making this argument must also present an alternative agricultural and economic model to sustain Pakistan’s water security — a model that currently does not exist in any credible policy form.

This brings us to some fundamental questions:

a) Is it realistic to treat groundwater beneath riverbeds as a permanent, sustainable source — or is it a myth?

b) If Pakistan relies only on underground water, how many years before its agricultural economy collapses?

c) What lessons can we draw from pre-canal agricultural models, and is their revival economically viable?

d) Most importantly, should Pakistan rethink its water-use patterns, especially the crop patterns that consume disproportionate amounts of water?

Unless we face these questions honestly, Pakistan’s reliance on unsustainable groundwater extraction risks pushing the country toward a severe water crisis, one that could cripple both our agricultural economy and food security.